Digital Logic Design Notes

Note: This set of notes is not entirely complete and excludes materials from the first two weeks of the course.

Basic Binary and Number System Conversions

Typically we’re used to representing all of our numbers with a total of 10 digits (0-9). When we change the base of a number system we are basically restricting (or expanding) the amount of digits we can use to represent numbers in any mathematical expressions.

With binary numbers systems, we are restricted to the use of only two digits (0 and 1) in order to represent numbers.

Any number in binary is typically represented as a sum of powers of two.

Given a binary number \(1010\ 0110\) we can break this into a table in order to determine its value in our traditional base-10 numbering system.

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| \(1\cdot 2^7\) | \(0\cdot 2^6\) | \(1\cdot 2^5\) | \(0\cdot 2^4\) | \(0\cdot 2^3\) | \(1\cdot 2^2\) | \(1\cdot 2^1\) | \(0\cdot 2^0\) |

From this we can sum the powers of 2 digits whose value is equal to 1 in order to find the decimal value.

A general expression for the decimal value of a binary number with digit values of \(c_i\) and \(n\) number of digits is:

\[\text{Value} = \sum\limits_{i=0}^n c_i\cdot 2^i\]

Using this expression we find the value of \(1010\ 0110\) to be:

\[1010\ 0110 = \sum\limits_{i=0}^n c_i\cdot 2^(i) = 2^7 + 2^5 + 2^2 + 2^1 = 128 + 32 + 4 + 2 = 166\]

One thing that is interesting to note is that we need to use more digits to represent the same amount of information with binary.

Values in the range of \(0 < x < 1\)

How do we represent decimal* values in binary (or any number system for that matter), that is, values between 0 and 1?

Given a number system of base \(n\) (in binary, \(n = 2\)) we represent everything to the right of the decimal point as negative powers of \(n\), similar to how we normally represent a larger, positive number.

Example: \(1101.1001\)

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | . | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| \(2^3\) | \(2^2\) | \(2^1\) | \(2^0\) | . | \(2^{-1}\) | \(2^{-2}\) | \(2^{-3}\) | \(2^{-4}\) |

This is equal to the decimal (base-10) number: \((8 + 4 + 1).(\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2^4})\) which gives \(13.5625\)

You can follow this same procedure for a number with base \(n = 10, 8, 16\) as well

Converting from Binary to Octal and Hexadecimal

The octal numbering system uses the digits (0-8) to represent numbers. Hexadecimal uses a total of 16 digits which includes the normal 10 digits (0-9) that we use in decimal, plus another 6 alphabetic characters to represent the numbers 10-11 which are A-F (\(A = 10, \dots , F = 15\))

Converting from binary to octal or hexadecimal (or any combination of two of these numbering systems) is quite easy due to that fact each numbering system is a power of 2.

- For conversions from binary to Hexadecimal:

- Group digits into blocks of 4, starting from the rightmost (least-significant side). If the number of digits is not divisible by 4, pad the left hand side with zeros until the number of digits is divisible by 4 evenly.

- For each group of 4 starting from the rightmost side, convert the group of 4 into its hexadecimal digit equivalent.

- Replace each group of 4 with the respective equivalent digit, the resulting string of hexadecimal characters is now the same number representation as we had in binary

- For conversions from binary to Octal:

- Group digits into blocks of 3, starting from the rightmost (least-significant side). If the number of digits is not divisible by 3, pad the left hand side with zeros until the number of digits is divisible by 3 evenly.

- For each group of 3 starting from the rightmost side, convert the group of 3 into its octal digit equivalent.

- Replace each group of 3 with the respective equivalent digit, the resulting string of octal characters is now the same number representation as we had in binary

We can follow a similar set of steps for the reverse procedure, by simply generating groups of 3 or 4 binary digits for hexadecimal.

Operations on Binary Numbers

Adding two binary numbers is relatively simple. Simply align the digits and follow the same procedure that you would for adding decimal numbers, except remember that you carry if the addition goes over 1.

Example: \(0101 + 0110\)

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| + | ||||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Now what about subtraction? This is important because it leads to the notion of negative numbers. How do we represent these?

\[1011_2 = 11_{10} = 5_{10} + 6_{10} \rightarrow \checkmark\]Negative Numbers in Binary - One’s and Two’s Complement

One possible way to represent a number as negative in a sense is to use a “signed” bit - a bit that basically will tell us whether or not the number we are currently using is going to be a positive or negative decimal value.

Example

| +127 | -127 |

| 01111111 | 11111111 |

Another way to represent the negative number is through something called “one’s complement” where we simply flip all the bits of a positive number to represent its negative.

Example:

| +127 | -127 |

| 01111111 | 10000000 |

And lastly, the most widely used version of number complementing systems which can be found in many modern applications is the two’s complement.

Two’s complement functions similarly to the one’s complement, except that after flipping all of the bits, we need to add 1 to the result.

Example:

| +127 | -127 |

| 01111111 | 10000001 |

It should be important to note that process for going from positive \(\rightarrow\) negative is the same as negative \(\rightarrow\) positive

Complementary MOS Gate (CMOS)

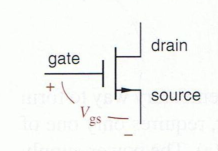

In CMOS logic we’ll typically deal with two types of MOSFET Transistors.

- NMOS (n-channel)

- PMOS (p-channel)

In a CMOS transistor we have three different pins. The behavior of the pins depends on the type of transistor (n vs p).

- Gate

- Source

- Drain

Behavior of an NMOS (n-channel) Transistor

From the diagram above note the three different pins and the direction of the source arrow.

In an NMOS transistor you should make note:

- The source voltage is typically higher than the drain voltage

- When adding voltage to the gate pin, it will decreases resistance between the source and drain

- This allows current to flow from the source and to the drain.

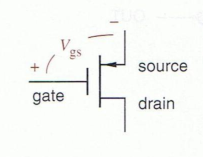

Behavior of a PMOS (p-channel) Transistor

A PMOS transistor is almost like a reverse or opposite to the NMOS.

Note here that the drain is now typically at a higher voltage than the source.

Also note now that:

- With no voltage applied to the gate, you will typically get a lower resistance from the source to the drain.

- To increase resistance between source and drain, increase the gate voltage

- With this gate, higher voltage = higher resistance (or lower voltage = lower resistance)

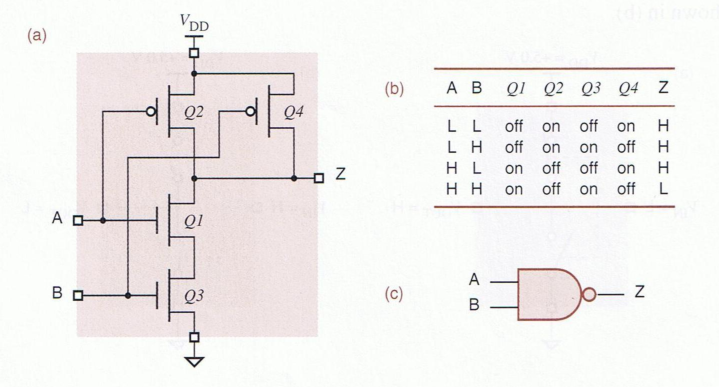

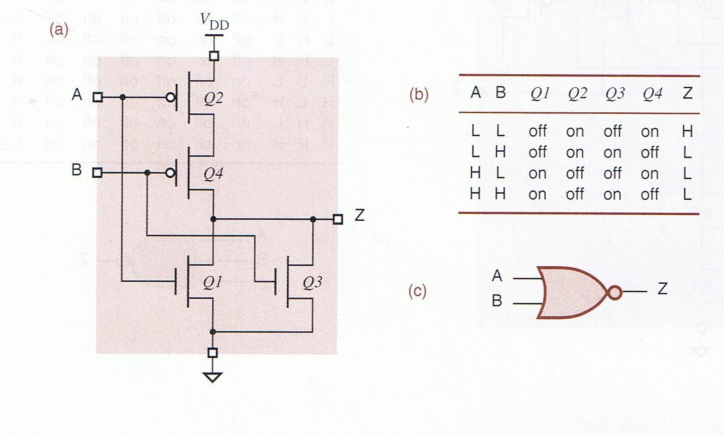

NAND and NOR Gates with CMOS Transistors

Boolean Algebra

| Expression | Equivalent |

| \(X(Y + Z)\) | \(XY + XZ\) |

| \(X + XY\) | \(X\cdot (1+Y) = X\) |

| \((X + Y)\cdot (X+Y')\) | \(XX + XY + XY' + Y\cdot Y' = X + X(Y + Y') = X\) |

Basic Logic Combinations

| \(X \cdot X\) | \(X\) |

| \(X \cdot X'\) | \(0\) |

| \(Y' + Y\) | \(1\) |

| \(Y + 1\) | \(1\) |

| \(X\cdot 0\) | \(0\) |

| \((X')'\) | \(X\) |

DeMorgan’s Rule

Given the boolean expression:

\[(X_1\cdot X_2\cdot X_3\cdot \dots \cdot X_n)'\]

We can say this expression is equivalent to:

\[X_1' + X_2' + X_3' + \dots + X_n'\]

Minterm and Maxterm

A minterm is a product of variables ANDed together and produces a “1” i.e.

- \[W\cdot X \cdot Y\cdot Z = 1\]

A maxterm is a sum of variables, ORed together and produces a “0”. i.e.

- \[W + X + Y + Z = 0\]

- A canonical sum is a sum those minterms that produce a “1”

- A canonical product is a product of maxterms that produce a “0”

Example Canonical Sum of Minterms:

\[F =(X'Y'Z') + (X'YZ) + (XY'Z') + (XYZ') + (XYZ)\]

Example Canonical Product of Maxterms

\[F = (X + Y + Z') \cdot (X + Y' + Z) \cdot (X' + Y' + Z') \cdot (X' + Y' + Z')\]

Given the table

| X | Y | Z | Binary Value |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

- The canonical sum is \(F = \sum\limits_{XYZ} (0, 3, 4, 6)\)

- The canonical product is \(F = \prod\limits_{XYZ} (1, 2, 5, 7)\)

Notice how the sum and product have different values, but the set of each containing both numbers completes the set of numbers possible in \(X Y Z\)

Karnaugh Maps (K-Maps)

An alternate way of deriving a function table.

Say we have two variables: \(X\) and \(Y\)

We would first create a table of size 2x2

| X/Y | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

Example, \(F = XY + X'Y\)

Three Variable Example:

| X/YZ | 00 | 01 | 11 | 10 |

| 0 | ||||

| 1 |

Notice how we changed from 01 to 11 instead of 01. This is because for the K-Maps we use the gray code, which is more efficient in terms of digital logic design becase we only ever change a single digit at a time even when looping back from the beginning to the end.

| Gray | Binary |

| 00 | 00 |

| 01 | 01 |

| 11 | 10 |

| 10 | 11 |

In binary when we go back from 11 to 00 we must change two digits as opposed to 1.

Gray Code for 4 variables

| Dec | W | X | Y | Z |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 11 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Minimal Sum-of-Products with K-Maps

Depending on the logical function sometimes we can create equivalent sum-of-product (or product of sum) expressions by grouping terms on a K-map. What this does is allow us to eliminate certain variables after identifying and grouping terms correctly.

In order to